From colossal insects rampaging through city streets to microscopic heroes saving the day, "ant films" have carved a surprisingly diverse niche in cinematic history. But what makes us flock to these stories? How do these tiny creatures, magnified on screen, resonate with audiences, and what lasting imprint do they leave on our cultural landscape? Delving into the fascinating world of Audience Reception & Cultural Impact of Ant Films reveals more than just popcorn entertainment; it unearths the complex interplay between media, perception, and societal values.

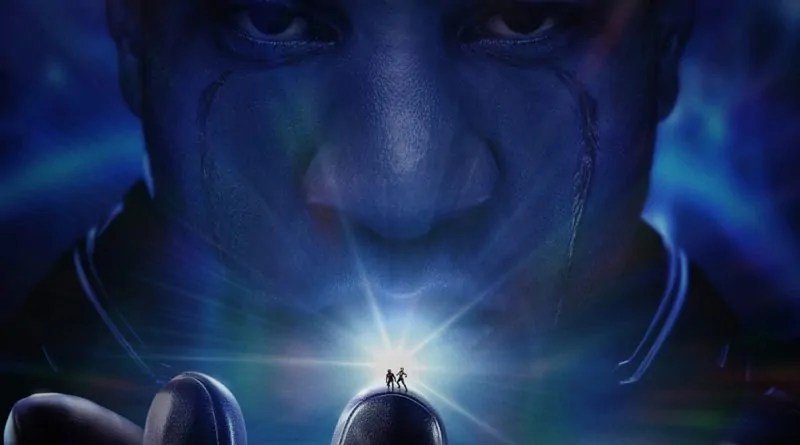

Understanding how audiences engage with ant films—whether it's the thrilling sci-fi horror of Them!, the animated family fun of Antz and A Bug's Life, or the superhero antics of Marvel's Ant-Man saga—offers invaluable insights into our collective anxieties, aspirations, and even our scientific curiosity. This isn't just about box office numbers; it's about the deep, often subconscious, ways these narratives shape our view of nature, heroism, and community.

At a Glance: Understanding Ant Films and Their Audiences

- Ant Films are Diverse: They range from horror to comedy to superhero epics, each targeting different audiences and carrying varied messages.

- Audiences Aren't Passive: Modern research views viewers as active interpreters, not just sponges soaking up information.

- Impact Goes Beyond Entertainment: Ant films influence public perception of insects, science, and even social structures.

- Reception is Complex: How a film is received depends on individual backgrounds, social contexts, and even historical moments.

- Understanding is Key: For creators, studying audience reception helps craft more resonant stories; for viewers, it enriches the viewing experience.

Why Do We Even Care How People Watch Movies About Ants?

At its core, audience reception is a field within media and cultural studies that investigates the intricate relationship between viewers and the content they consume. It's about figuring out how we make sense of films, why we're drawn to certain narratives, and what role mass media plays in shaping our society. When we apply this lens to ant films, we move beyond simple plot summaries to ask deeper questions:

- How do films featuring ants contribute to (or challenge) our understanding of these creatures in the real world?

- Do portrayals of ants as menacing villains increase entomophobia, or do films like Ant-Man foster a newfound appreciation for their abilities?

- What cultural anxieties or aspirations do these narratives tap into? Are they about fears of invasion, the power of the collective, or the hidden strength of the small?

To answer these questions, we turn to established frameworks from audience theory and research, which generally alternate between two fundamental perspectives: the "passive audience" and the "active audience."

The Early View: When Audiences Were "Ant-Sized" – Passive Audience Theories

Early media research, particularly from the 1920s to the 1960s, often viewed the audience as a largely passive, homogenous group. In this "effect theory" paradigm, the media (and its message) held immense power, capable of directly influencing thoughts and behaviors. The central concern was "what media can do to people."

Think of the post-WWI era, where the power of propaganda became starkly evident, or the Frankfurt School's concerns about mass culture becoming an instrument of social control. This perspective, though critiqued for its narrowness, still influences discussions today, especially when we talk about the impact of media on vulnerable groups like children.

The Hypodermic Model: Direct Injections of Ant-Fear?

Imagine a giant syringe injecting ideas directly into your brain. That's the essence of the Hypodermic Model (also known as the "Magic Bullet" or "Stimulus Response" theory). Attributed to Harold Lasswell's studies of WWI propaganda, this model suggests that mass media has an overwhelming, direct, immediate, and addictive effect. Audiences are seen as powerless, absorbing messages like a drug.

- Ant Film Application: If the Hypodermic Model were fully true, a film like Them! (1954), with its giant, radioactive ants terrorizing humanity, would instantly cause widespread phobia of all ants and possibly lead to calls for mass extermination. Similarly, a cartoon portraying ants as cute, helpful creatures would immediately make every child want an ant farm, regardless of their prior disposition. While we know this isn't how it works in reality, concerns about children's direct imitation of media behaviors (e.g., seeing an ant "hero" and trying to mimic dangerous stunts) still echo this early thinking.

Cultivation Analysis: When Ant Films Shape Your Reality

Developed by George Gerbner and Larry Gross in the late 1960s, Cultivation Analysis posits that prolonged, regular exposure to television (and by extension, other media) gradually shapes our perceptions of reality. It doesn't suggest a sudden behavioral change but a cumulative, long-term effect that "cultivates" certain beliefs and attitudes.

Gerbner initially focused on violence, arguing that heavy TV viewers tend to exaggerate the prevalence of violence in society and feel more insecure. This "first order judgment" then influences "second order judgments" about how society should be managed.

- Ant Film Application: Consider a steady diet of films depicting ants solely as invasive pests or dangerous monsters (e.g., Phase IV, Empire of the Ants). Over time, Cultivation Analysis would suggest that heavy viewers might develop an exaggerated sense of the threat ants pose, leading them to view all insects with suspicion, support aggressive pest control measures, or even cultivate a general sense of unease about the natural world infiltrating human spaces. Conversely, a steady stream of positive ant portrayals (like in movies about ants that highlight cooperation and cleverness) could cultivate a more positive, curious, or even empathetic view towards insect life.

The Two-Step Flow Model: Ant Opinions Through Opinion Leaders

Recognizing the limitations of the direct-effect theories, researchers like Lazarsfeld, Katz, and Merton introduced the Two-Step Flow Model in the 1950s. This model proposed that media influence isn't direct but is mediated by "gatekeepers" or "opinion leaders" within social groups. Information flows from media to these opinion leaders, who then interpret and transmit it to "opinion followers."

- Ant Film Application: Imagine a new ant film is released. Instead of directly impacting every viewer, its initial reception might be filtered through prominent film critics (opinion leaders) whose reviews sway public opinion. Or, within a specific fan community, an influential blogger or forum moderator might shape how others perceive the film's scientific accuracy, its ecological message, or its entertainment value. If an opinion leader praises a particular aspect of an ant film—say, its detailed CGI ants or its nuanced portrayal of colony life—their followers are more likely to adopt a similar positive view, reinforcing the media's message through a social filter.

The Modern Perspective: Audiences as Architects of Meaning – Active Audience Theories

By the 1960s, media research underwent a significant shift. Scholars began to question the passive audience paradigm, recognizing the vast variation in how people interpreted and used media. The fundamental question flipped from "What media can do to people?" to "What people do with media?" This active audience perspective acknowledges that individuals bring their unique experiences, social contexts, and needs to their media consumption.

Uses and Gratification Model: What Do You Get Out of Watching Ants?

One of the foundational active audience theories is the Uses and Gratification Model (Katz, Blumler, Halloran, 1960s). It argues that audiences aren't just recipients; they actively select and use media to satisfy specific psychological and social needs. Instead of asking what media does to people, it asks what people do with media.

People might use ant films for:

- Information: Learning about ant biology, social structures, or fictional scientific concepts (e.g., the Pym Particles in Ant-Man).

- Personal Identity: Seeing aspects of themselves or their values reflected in the characters (e.g., a small hero overcoming odds, the power of teamwork).

- Entertainment/Escapism: Enjoying the spectacle, thrills, or humor of a fantastical world; escaping daily routines.

- Social Interaction: Discussing the film with friends, family, or online communities; using it as a shared cultural reference point.

- Ant Film Application: A child might watch A Bug's Life for entertainment, but also to satisfy a need for social interaction by discussing the characters with friends. An adult might watch an ant documentary for information, while simultaneously fulfilling a personal identity need by reinforcing their interest in nature or science. The same film can offer different gratifications to different viewers, highlighting the model's rejection of a homogenized media effect.

Encoding/Decoding Model: The Ant's Message, Your Interpretation

Stuart Hall's influential Encoding/Decoding Model (1970s) offers a nuanced compromise between the "audience as victim" and "audience as autonomous" views. It suggests that media texts are "encoded" with preferred meanings by producers, but audiences then "decode" those meanings based on their own cultural and ideological positions. This model acknowledges that while texts might "prefer" certain readings, they are often "polysemic"—capable of multiple interpretations.

Hall outlined three primary reading positions:

- Dominant/Preferred Reading: The audience accepts and interprets the message precisely as the producer intended.

- Ant Film Example: Watching Ant-Man and fully embracing Scott Lang as a relatable, flawed hero who, despite his criminal past, genuinely wants to do good for his family and the world, using his ant-controlling abilities for altruism.

- Negotiated Reading: The audience largely accepts the dominant meaning but modifies or adapts it to fit their own experiences or beliefs, sometimes disagreeing with certain aspects.

- Ant Film Example: Enjoying Ant-Man for its humor and action, agreeing that Scott Lang is a hero, but perhaps questioning the scientific plausibility of Pym Particles or the moral implications of manipulating animals, even for good. "Yeah, he's a hero, but those ants are basically slaves!"

- Oppositional Reading: The audience completely rejects the preferred meaning, interpreting the text in a way that is contrary to the producer's intent, often from an alternative ideological perspective.

- Ant Film Example: Viewing Ant-Man not as a heroic tale, but as a critique of unchecked technological advancement, or seeing the ant control as a metaphor for human exploitation of nature. Or, perhaps, rejecting the film entirely for what they perceive as its trivialization of scientific principles or its adherence to a corporate-driven superhero franchise.

Screen Theory: The Cinematic Ant's Gaze

Emerging from the 1970s, Screen Theory (drawing on feminism, psychoanalysis, Marxism, and semiotics) focused on how cinema itself "positions" the spectator. Through textual elements like camera placement, editing, and narrative structures, films are seen to construct a viewing subject, subtly transmitting ideological messages—often reinforcing a "bourgeois ideology" of naturalism and realism.

- Ant Film Application: Think about the unique ways ant films play with perspective and scale. When a camera adopts an ant's-eye view, making a blade of grass seem like a skyscraper, or a drop of water a vast ocean, Screen Theory would analyze how this visual language positions the viewer. Does it foster empathy for the small? Does it highlight humanity's destructive footprint from a tiny creature's perspective? Or does it, conversely, reinforce our sense of superiority by allowing us to temporarily inhabit their world before returning to our own dominant human scale? It’s about how the form of the film shapes your psychological and ideological experience.

Audience Ethnography: Watching Ant Films in the Wild

Moving away from purely textual analysis, Audience Ethnography (championed by David Morley in the 1980s with his Nationwide Audience study) emphasizes that media reception is a deeply social and context-based practice. Meanings aren't just derived from the text itself, but from the social experiences and cultural frameworks audiences bring to their viewing. Researchers using this approach empirically investigate how diverse "interpretative communities" engage with media in their natural environments.

- Ant Film Application: An ethnographic study might observe groups of children watching A Bug's Life in a daycare setting, analyzing how their social dynamics, age, and prior experiences with insects influence their reactions and discussions. Or, it could involve interviews with different generations of viewers after watching Them! to understand how their historical context (e.g., Cold War anxieties, fears of nuclear mutation) shaped their interpretation of the giant ants. This approach provides rich, qualitative data about the lived experience of media consumption, showing how meaning and pleasure are created not just in front of the screen, but within broader social interactions and conversations.

The Cultural Ripple: Beyond the Screen, What Ant Films Leave Behind

The reception of ant films isn't just about what happens during the movie; it has tangible cultural impacts that extend far beyond the cinema hall.

Shaping Perceptions of Nature and Science

Films about ants, whether accurate or fantastical, inevitably influence how the public views these insects and, by extension, the natural world.

- Fear vs. Fascination: Horror films like Them! or Phase IV can contribute to a societal fear of insects, framing them as alien, dangerous, and a threat to human dominance. Conversely, animated features like Antz and A Bug's Life, or documentaries, can foster curiosity, empathy, and an appreciation for the complex social structures and industriousness of ants.

- Scientific Curiosity: The popularity of superhero films like Ant-Man can spark interest in fields like entomology, quantum physics (however loosely portrayed), or even engineering for size-changing technology, especially among younger audiences. They make science, even fictionalized, seem exciting and relevant.

Social Commentary and Metaphor

Ant societies, with their rigid hierarchies, collective action, and apparent selflessness, serve as potent metaphors for human societies.

- Individual vs. Collective: Antz famously explores themes of individuality and rebellion against a totalitarian collective, using the ant colony as a critique of conformity. A Bug's Life, while also featuring a collective, emphasizes the power of diverse individuals working together. These narratives allow audiences to reflect on their own societal structures, political systems, and personal roles within them.

- Environmentalism: Many ant films carry implicit (or explicit) environmental messages, depicting humans as either destructive forces or as part of a larger, interconnected ecosystem where even the smallest creatures play a vital role.

Merchandising, Fandom, and Cultural Touchstones

Successful ant films become cultural touchstones, generating merchandise, fan art, fan fiction, and sparking ongoing discussions.

- Play and Identity: Toys, video games, and costumes related to ant films allow audiences, particularly children, to extend their engagement with the narrative, role-play characters, and solidify their connection to the story world.

- Community Building: Online forums, social media groups, and fan conventions dedicated to specific ant film franchises (like the Marvel Cinematic Universe's Ant-Man) create communities where individuals can share their interpretations, theories, and creative works, further deepening the cultural impact and longevity of these films.

Navigating the Nuances: Beyond Simple "Good" or "Bad"

The study of audience reception is far from a simple judgment of whether a film is "good" or "bad." It's about understanding complexity:

- Not All Ant Films Are Created Equal: A B-movie horror from the 50s will have a vastly different reception and impact than a modern CGI-animated blockbuster or a scientifically accurate documentary. The genre, production values, target audience, and era all play a role.

- The Audience is Never Monolithic: There's no single "audience" for ant films. Interpretations vary wildly based on age, gender, socioeconomic status, cultural background, prior knowledge of ants, political leanings, and even individual mood. What one viewer finds terrifying, another might find comedic.

- "Impact" is Multi-faceted: Impact isn't just about direct behavior change. It encompasses shifts in attitude, emotional responses, enhanced knowledge, social bonding, and even subtle reinforcement or challenge of existing ideologies.

Applying the Lens: What Ant Film Creators and Marketers Can Learn

For filmmakers, writers, and marketers, understanding audience reception isn't just academic; it's profoundly practical.

- Crafting Resonance: By anticipating how different audiences might decode their messages, creators can intentionally embed themes that resonate deeply, provoke thought, or entertain broadly. Do you want to instill awe, fear, or empathy for your ant characters? The choice of narrative, visuals, and character arcs directly influences this.

- Targeted Messaging: Marketers can use insights from audience research to tailor campaigns. Knowing which "uses and gratifications" an ant film offers (e.g., escapism for adults, educational value for parents) allows for more effective promotion to specific demographics.

- Avoiding Pitfalls: Understanding potential "oppositional readings" can help creators avoid unintended negative interpretations or backlash, particularly in culturally sensitive areas. Conversely, a savvy creator might intentionally encode a text with polysemy, inviting diverse interpretations and fostering deeper engagement.

Beyond the Hive: The Enduring Legacy of Ant Films

From the terrifying giant ants of mid-century monster movies, tapping into Cold War anxieties about mutation and invasion, to the relatable, miniaturized heroes of today, using their unique abilities to fight crime and protect family, ant films reflect and shape our cultural narrative. They demonstrate that even the smallest creatures on screen can generate profound discussions, spark scientific curiosity, and offer powerful metaphors for our own human condition.

The next time you settle in to watch ants march across your screen, consider not just the story unfolding, but the intricate web of meaning you—and countless others—are actively weaving, decoding, and integrating into the vast, complex tapestry of our shared culture. The reception of these films isn't just a footnote; it's a testament to the enduring power of storytelling and the active, interpretative role of every single viewer.